The exact worth of massive global fossil fuel subsidies is incredibly hard to figure. There’s no real consistency in the definitions of subsidies, or how they should be calculated. As a result, estimates of global subsidy support for fossil fuels vary widely.

According to a new analysis by the Worldwatch Institute, these estimates range from $523 billion to over $1.9 trillion, depending on what is considered a “subsidy” and how exactly they are tallied.

Worldwatch Institute research fellow Philipp Tagwerker, who authored the brief, explains:

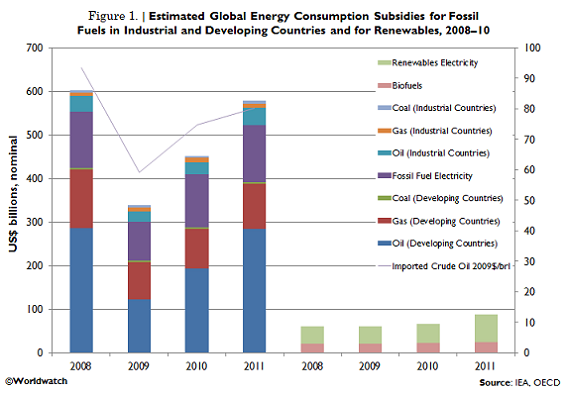

The lack of a clear definition of “subsidy” makes it hard to compare the different methods used to value support for fossil fuels, but the varying approaches nevertheless illustrate global trends. Fossil fuel subsidies declined in 2009, increased in 2010, and then in 2011 reached almost the same level as in 2008. The decrease in subsidies was due almost entirely to fluctuations in fuel prices rather than to policy changes.

In other words, though the estimates vary widely, they all agree that fossil fuel subsidies are back up to the record levels they were at in 2008, before the financial crisis caused a temporary dip. So while world leaders, including President Obama, talk about ending subsidies that benefit one of the world’s richest industries, there hasn’t been any actual reduction.

Why such difficulty calculating the subsidies? For starters, subsidies typically fall into two broadly different categories: production subsidies and consumption subsidies. Production subsidies are what you think of when you hear about special tax rates for oil companies or grants or loan guarantees to “clean coal” projects. Basically, they include anything that lowers the cost of energy production — through tax advantages, loan assistance, grants, or anything else.

Consumption subsidies refer to any financial mechanisms that lower the cost of energy for the end consumers. Think of the artificially low gasoline prices in Venezuela, or even something such as tax breaks for home heating fuel.

According to Tagwerker, production subsidies are most common in wealthier, industrialized countries, while consumption subsidies are more common in developing countries with populations struggling to afford fossil fuels.

The $523 billion number above — standing as the bottom boundary of the range of global fossil fuel subsidies — represents only the consumption subsidies for coal, electricity, oil and, natural gas in 38 developing countries, as estimated by the International Energy Agency (IEA). It doesn’t include any production subsidies at all.

Production subsidies are often quoted at $100 billion a year, a number that comes from a June 2010 report to the G-20 leaders from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), the IEA, the World Bank, and the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC). But that doesn’t include so-called “support measures” like:

- export credit agencies (estimated at $50-100 billion annually)

- cost of securing fossil fuel shipping routes (estimated at $20-500 billion/year)

Then there’s the issue of externalities. Tagwerker argues that external costs — like those associated with resource scarcity, environmental degradation, and human health — should be considered in subsidy calculations, as their absence artificially lowers the true cost of fossil fuel energy.

“Without factoring in such considerations, renewable subsidies cost between 1.7¢ and 15¢ per kilowatt-hour (kWh), higher than the estimated 0.1–0.7¢ per kWh for fossil fuels,” writes Tagwerker. “If externalities were included, however, estimates indicate fossil fuels would cost 23.8¢ more per kWh, while renewables would cost around 0.5¢ more per kWh.”

A recent report by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) took a unique approach to subsidy calculations, lumping them into pre-tax and post-tax groupings rather than production and consumption.

The IMF then tacked on a modest $25-per-ton carbon tax to capture the external costs of climate pollution. After tallying up all the various subsidies, the IMF came up with a whopping $1.9 trillion every year, or roughly 2.5-percent of the global GDP in 2012.

Finally, Tagwerker considers the entire subsidy through the lens of climate pollution. “From an emissions perspective, 15 percent of global carbon dioxide emissions receive $110 per ton in support, while only 8 percent are subject to a carbon price, effectively nullifying carbon market contributions as a measure to reduce emissions.”

Image credit: Subsidies via Shutterstock.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts