Not many locals even knew the Bureau of Land Management was holding a scoping meeting in Mountainair, New Mexico last December for the proposed Lobos CO2 Pipeline that would run through their community.

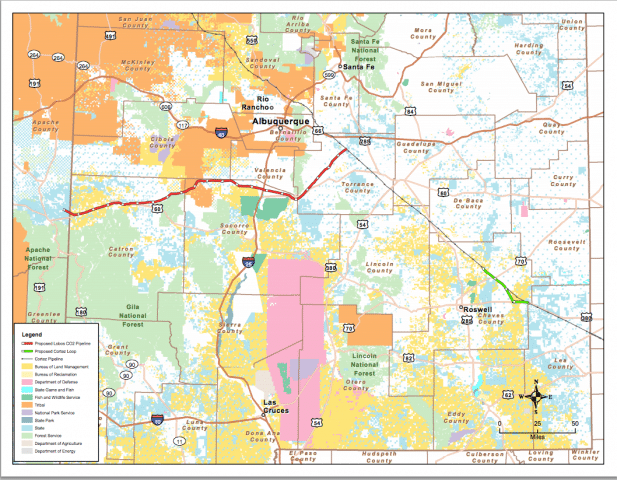

When the people of Mountainair did find out about what was proposed that day, many had concerns. BLM officials had laid out the route preferred by Kinder Morgan, which aims to build the 213-mile-long pipeline to get CO2 from Apache County, Arizona to Torrance County, New Mexico. From there, the Lobos CO2 pipeline would connect with the Cortez pipeline to deliver CO2 to oil wells in Texas. The route crosses tribal, private, state, and federal lands.

That’s when the locals started organizing themselves under the name Resistiendo: Resist the Lobos CO2 Pipeline. They networked with other concerned folks in the region, they packed a public information meeting in January, they submitted hundreds of comments pointing out a number of issues with the route: it would disrupt a sensitive desert ecosystem; a spill in the Rio Grande River would be disastrous for silvery minnow populations; it could impact nearby Native American cultural sites, including Salinas Pueblo Missions National Monument; it crossed agricultural lands; in some cases, the route proposed by the company passed within just 100 feet of people’s homes.

Kinder Morgan wasn’t making any friends by throwing around threats to use eminent domain against landowners who refused to let the company’s workers survey their land. And many locals felt the BLM was not on their side.

“It felt like the BLM were advocates for Kinder Morgan, that this was a done deal and just the particulars needed to be worked out,” says Linda Filippi, who works with Resistiendo.

Local activists were forced to find another way of making their voices heard. Together with the Partnership for a Healthy Torrance Community and the New Mexico Department of Health, the group is working with an outside firm, Human Impact Partners of Oakland, California, to perform their own Health Impact Assessment (HIA) as a supplement to the BLM’s environmental impact statement (EIS).

Local activists conducting their own health assessment on a project that will impact their community is a novel but potentially effective way of reclaiming, at least in part, a review process that often favors polluter interests over people and planet.

Activists using HIAs to change the discussion

The EIS process followed by the BLM is outlined in the National Environmental Policy Act, which requires that federal agencies determine “the degree to which the proposed action affects public health or safety.” But a full Human Impact Assessment is rarely performed by the BLM.

“We feel they are disregarding the spirit and the intent of the law, which is to fully understand the impacts on human health that the agency makes,” says Amy Mall, a senior policy analyst with the Natural Resources Defense Council.

Mall says that studying the impacts on human health was not a priority for the BLM in the past because most of the projects the agency was approving were not considered to be close to where people live or to sources of drinking water.

“But we all know that oil and gas projects are moving closer to where people live, and people are moving closer to where oil and gas projects are,” Mall says. And of course, we understand a lot more about the impacts on human health that result from fossil fuel extraction and transport via pipeline. “Even if the agency was justified in not doing it in the past, it certainly isn’t now.”

While it’s not quite what you’d call a trend yet, there are other cases of communities fighting back with their own HIAs.

After a citizen petition asked county commissioners to consider public health in the permitting process for a 200-well natural gas development proposed in Battlement Mesa, Colorado, the Garfield County Public Health Department teamed up with the Colorado School of Public Health to conduct their own HIA.

Jennifer Lucky, who works with Human Impact Partners, the organization performing the HIA for Resistiendo in New Mexico, says that there are often concrete outcomes from a community producing its own HIA.

Lucky points to the case of Farmers Field, a 72,000-seat football stadium in downtown Los Angeles. HIP did an HIA that helped local activists wring meaningful concessions from the developer, Anschutz Entertainment Group, including: “$15 million for affordable housing; $5 million for parks/open space, neighborhood improvement plans, and funding for a community team to promote health and protect tenant rights in the area; and local hiring commitments.”

But Lucky says that the HIA process can also be a catalyst for community organizing and campaigning. This, she says, can change the discussion around the decision, “which is a huge win,” she’s found.

The BLM has even acquiesced to citizen pressure itself and performed a full HIA. The agency worked in partnership with local tribes and communities as well as health experts and the EPA to produce its analysis of the impacts oil and gas drilling would have on the Western Arctic Reserve in Alaska.

But it is not common practice for the BLM to perform a full HIA when approving new projects, even though local governments have requested that the agency consider impacts to human health and safety.

“No decisions have been made” about Lobos CO2 pipeline

Mark Mackiewicz, Senior National Project Manager for the BLM, confirmed that full HIAs are not commonly performed by his agency, but says that the environmental review process adequately covers health and safety issues.

The Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration will review Kinder Morgan’s proposal for the Lobos CO2 pipeline, for instance, Mackowiecz says, and the BLM will take the PHMSA’s findings into account when preparing the draft environmental impact statement, which has no release date yet.

As for the concerns locals have about the process itself, Mackiewicz says it’s been conducted according to regulations: “We’re following the process as laid out in the NEPA. No decisions have been made. But we have to have a starting point, and that’s the company’s proposal.” The BLM is looking at alternative routes, and will publish its findings in the DEIS.

And when the BLM’s draft EIS is released, the community-sourced HIA being conducted by Resistiendo and its partners will be submitted as a comment, forcing the BLM to consider all of the concerns about the pipeline before issuing its final decision on the project.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts